Access to Firearms Increases Child and Adolescent Suicide

Edited by Rebekah Levine Coley, Ph.D., Boston College. For more information, contact Kelly R. Fisher, Ph.D., Director for Policy, Society for Research in Child Development, at policy@srcd.org.

Authors

- Matthew Miller, M.D., M.P.H., Sc.D., Bouvé College of Health Sciences, Northeastern University

- Deborah Azrael, Ph.D., Harvard Injury Control Research Center, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Harvard University

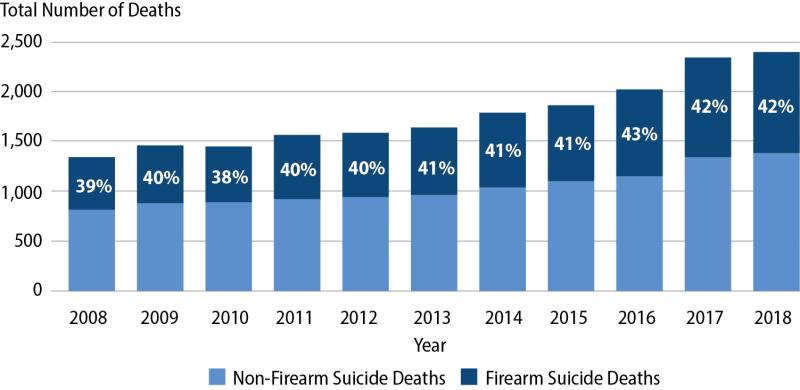

Nearly 2,400 children and adolescents aged 5-18 died by suicide in the United States in 2018, making suicide the second leading cause of death in this age group.1 Suicide rates among children and adolescents have increased by over 80% over the past decade in the U.S. Of those deaths, about 40% involved firearms. Suicide rates among children and adolescents who live in homes with guns are four times higher than among those in homes without guns. Evidence shows that the suicide risk associated with firearm possession in homes with children can be reduced, though not eliminated, by storing firearms locked, unloaded, and separate from ammunition. Research also shows that pediatrician provided counseling to parents can improve firearm storage practices in the home, especially when the counseling is supplemented with free firearm storage devices. Expanded gun violence research is needed to better understand and to successfully reduce rates of child and adolescent gun suicides.

Access to Firearms Dramatically Raises the Likelihood of Dying by Suicide

Extensive evidence finds that access to firearms increases the likelihood of death by suicide among children and adolescents. Forty percent of suicides in this age group involve firearms, due both to the ubiquity of access to guns and to the far greater lethality of suicide attempts by gun versus other means.1 And nine out of ten child and adolescent suicides by gun involve firearms from the victim’s own home or that of a relative.2,3,4 The risk of suicide death is three times higher for persons of any age who live in homes with, compared to without, firearms.5 For children and adolescents, the rates of death by suicide are over four times higher in households with firearms.6 In short, where there are more guns, there are more firearm suicides, but not more suicides from other methods.7,8

Given the increased risk of suicide in households containing firearms, the prevalence of firearms in households with children and adolescents is a major public health concern. Approximately one in three households with children and adolescents contain firearms.9 Thus, about 30 million children under the age of 18 live in a home with at least one firearm.10 Of these homes, approximately half contain at least one firearm that is unlocked and 20% contain at least one firearm that is both unlocked and loaded.11

Suicide Deaths in U.S. Children, Ages 5-18

Safe Firearm Storage Practices Decrease Risks

Accordingly, gun safety practices that reduce children’s and adolescents’ access to firearms can reduce the risk of suicide by gun, and thus decrease the total number of children and adolescents dying by suicide. Numerous gun storage practices are linked to suicide:

- When a home contains unlocked guns the odds of a child or adolescent dying by firearm suicide is more than twiceas high as in households where all guns are locked.12

- The risk of suicide by gun is more than twice as high in households with loaded guns, as compared to households with unloaded guns.11

- Storing ammunition together with firearms as opposed to separately also increases the risk of suicide two-fold.11

A recent study estimated that approximately 100 suicides among 5 to 19 year-olds could be prevented annually if the proportion of unlocked firearms in households with children or adolescents decreased from 50%, as is the case today, to 30%.13 Yet, parents (and other adults) appear to be unaware of the heightened risks of suicide associated with children’s access to household firearms. Indeed, less than 10% of gun-owning adults with children agree the presence of a firearm in the home increases the risk of suicide.14

Efforts to Reduce Child and Adolescent Suicide by Reducing Access to Firearms

U.S. interventions to reduce child and adolescent access to firearms in their homes generally take one of two approaches. One approach has been Child Access Prevention (CAP) laws— state legislation imposing penalties on adults if a child could gain or gains access to their guns, especially if access results in a fatal or non-fatal injury. Some research suggests that CAP laws may lower rates of child suicide.

But the limited available evidence is mixed, and the most rigorous assessments to date suggest that insufficient data are available to draw strong conclusions.15,16

A second approach to reducing child and adolescent access to firearms is to have pediatricians (and emergency department clinicians who see at-risk children) counsel parents about firearm safety. Interventions that counsel parents to either remove guns from their home or, if that is not possible, to store all firearms locked and unloaded in their homes have generally been found to improve parental firearm storage practices. These efforts appear to be more effective when counseling is augmented with the provision of firearm storage devices.17,18

Conclusion

The presence of a firearm in one’s home dramatically increases the risk of death by suicide for children and adolescents. Locking and unloading all household firearms and storing firearms separately from ammunition substantially mitigates, but does not eliminate, the heightened risk of suicide associated with the presence of household guns. The Dickey amendment, an annual federal spending bill provision that was long interpreted as prohibiting research on gun violence, has hampered scientific understanding of firearm-related violence and discouraged the evaluation of prevention efforts. As such, it has impeded progress on understanding how to intervene most effectively to reduce firearm and thus overall suicide deaths. It is essential to dramatically expand rigorous evaluations of efforts to decrease suicide rates for U.S. children and adolescents. Increasing effective and safe firearm storage is one muchneeded step that can help prevent the loss of so many young lives to gun violence.

Endnotes / References

(1) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars

(2) Grossman, D. C., Reay, D. T., & Baker, S. A. (1999). Self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries among children and adolescents: The source of the firearm. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 153(8), 875–878. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.8.875

(3) Johnson, R. M., Barber, C., Azrael, D., Clark, D. E., & Hemenway, D. (2010). Who are the owners of firearms used in adolescent suicides? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(6), 609–611. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2010.40.6.609

(4) Schnitzer, P. G., Dykstra, H. K., Trigylidas, T. E., & Lichenstein, R. (2019). Firearm suicide among youth in the United States, 2004–2015. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 42(4), 584–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00037-0

(5) Anglemyer, A., Horvath, T., & Rutherford, G. (2014). The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 160(2), 101–110. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1301

(6) Brent, D. A., Perper, J. A., Moritz, G., Baugher, M., Schweers, J., & Roth, C. (1993). Firearms and adolescent suicide: A community case-control study. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 147(10), 1066–1071. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160340052013

(7) Miller, M. & Hemenway, D. (2008). Guns and suicide in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 359(10), 989-991. http://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0805923

(8) Miller, M., Barber, C., White, R., & Azrael, D. (2013). Firearms and suicide in the United States: Is risk independent of underlying suicidal behavior? American Journal of Epidemiology, 178(6), 946-955. http://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwt197

(9) Scott, J., Azrael, D., & Miller, M. (2018). Firearm storage in homes with children with self-harm risk factors. Pediatrics, 141(3), e20172600. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2600

(10) Azrael, D., Hepburn, L., Hemenway, D., & Miller, M. (2017). The Stock and flow of U.S. firearms: Results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of Social Science, 3(5), 38–57. http://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2017.3.5.02

(11) Azrael, D., Cohen, J., Salhi, C., & Miller, M. (2018). Firearm storage in gun-owning households with children: Results of a 2015 National Survey. Journal of Urban Health, 95, 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0261-7

(12) Grossman, D. C., Mueller, B. A., Riedy, C., Dowd, M. D., Villaveces, A., Prodzinski, J., … Harruff, R. (2005). Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293(6), 707–714. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.6.707

(13) Monuteaux, M. C., Azrael, D., & Miller, M. (2019). Association of increased safe household firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional death among US youths. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 173(7), 657–662. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1078

(14) Conner, A., Azrael, D., & Miller, M. (2018). Public opinion about the relationship between firearm availability and suicide: Results from a national survey. Annals of Internal Medicine, 168(2), 153-155. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-2348

(15) RAND Corporation (2018). The relationship between firearm availability and suicide. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/essays/firearm-availability-suicide.html Accessed August 23, 2019.

(16) Schell, T. L., Griffin, B. A., & Morral, A. R. (2018). Evaluating methods to estimate the effect of state laws on firearm deaths: A simulation study. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2685.html. Also available in print form.

(17) Rowhani-Rahbar, A., Simonetti, J. A., & Rivara, F. P. (2016). Effectiveness of interventions to promote safe firearm storage. Epidemiologic Reviews, 38(1), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxv006

(18) Miller, M., Salhi, C., Barber, C., Azrael, D., Beatriz, E., Berrigan, J., Brandspigel, S., Betz, M. E., & Runyan, C. (2020). Changes in firearm and medication storage practices in homes of youth at risk for suicide: Results of the SAFETY study, an ED-based multi-site trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.02.007 Manuscript in press.